I recently spent an exciting three-months at Georg-August University in Göttingen, Germany. I joined the Research Group of the "WortSchatzInsel", the centre for the study of language acquisition led by Prof. Nivedita Mani. And it was all thanks to the LuCiD Travel Award! Let me tell you what I got up to when I was there.

It never ceases to amaze me how quickly children become language experts, and the journey from language novice to language expert is unique to each child. Put simply, some children acquire language faster than others, and I am fascinated by why this might be. How can two children who are both exactly the same age show such different rates of language learning?

We know already that differences in the language that children are exposed to can affect their rate of language learning. Originally, we thought that the number of words that children hear drives differences in their language development. It seemed like children who heard more words, knew more words. More recently, however, we've learned that it's the quality of heard language that's key (see this New York Times article for a great summary). This means that it is the way in which language is presented to the child can help explain why language learning varies so much. Children whose parents adopt a more conversational approach in teaching new words (for example by saying "Wow, can you see that caterpillar, Anna?!" instead of "This here is a caterpillar."), will generally learn the new word earlier.

So, we know that the way in which words are presented will affect how children learn them. This then made me wonder. Some words refer to amazing and exciting things (chocolate, birthday, santa!!), but some refer to things that we might not want children to find exciting (slug, knife, snot). These exciting and not-so-exciting words are therefore likely to be spoken to the child differently, and does this affect how well they can learn these words?

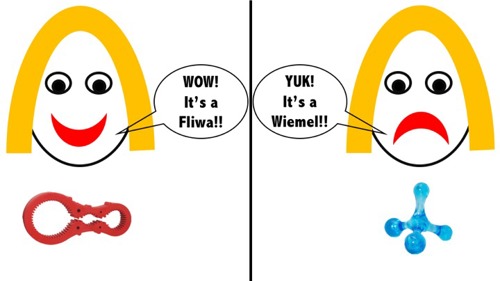

At the centre for language acquisition at Göttingen, they are experts in the role of emotion in language. So I teamed up with Julia Brase, a researcher in their group, to put together an experiment that would investigate how children learn words for happy and not-so-happy things. To do this, we presented three-year-old children with pictures of a range of objects that they had never seen before. Each object was assigned a nonsense German word that the child had never heard before. As each object was displayed on the screen, the actor looked at and labelled the object. Some object labels were spoken in a positive and excited way (e.g. "WOW! Look, its a Fliwa!!") and some objects were labelled in a negative and disgusted way (e.g. "YUK! Look its a Wiemel!!"). An eye-tracker underneath the screen allowed us to record how long the child looked at each object during labelling. We then tested whether the child has learned the word after a short break.

Picture shows a simplified diagram of our experiment. Which word will the children learn better? Fliwa or Wiemel?

What did we find?? The simple answer is - we don't know yet! Data collection finished very recently, so we are only just beginning to analyze it. First, we will look to see whether children looked at the object differently, depending on whether it was presented in a positive or negative tone of voice. If the children’s looking at these objects is different, we can then see whether this affects how well they remembered the word meanings.

So, why does this matter? It’s a good question. As fun as it is sounds, this experiment could have important implications. In our constant attempt to understand differences in the rate of language learning, we are trying to understand what affects how easy or hard words can be to learn1. We know words that are heard often are easier to learn, and this experiment hopes to shed on light on whether the emotion attached to a word can make it easier to learn too. If we find that happy words are easier to learn, then children who show slower language development may benefit from a greater focus on happy words in their language input. Although this sounds a bit like common sense, we don’t really have any scientific evidence for it!

And that’s what I got up to in Göttingen!! Watch this space for some interesting results! Thanks to everyone at Göttingen who made me feel so welcome, and thanks to all the families who took part!!