Late talking children, or ‘late talkers’, are children aged between 18-30 months old who speak far fewer words than 90% of children of the same age, without any known developmental or sensory impairments. However, late talking itself is not a clinical diagnosis: it is a symptom. As we know, symptoms can be a part of something larger, or they can be red herrings.

In the case of late talking, the story is even more complex: whilst the vast majority of late talkers reach the same range of vocabulary skills as their peers by school-age, there are a small minority who are at risk of developing developmental language disorder1. We currently do not have a clear way of predicting those who will catch up from those who will not: all we really know for certain about late talkers is that they say less than other children their age. Understandably, the lack of speech from these children can lead to parental concern and highlights the importance of identifying early on the minority who will not catch up.

So far, large population studies that investigate factors like receptive vocabulary (how much children understand), socioeconomic status, family history of language delay, and sex demonstrate small but significant effects when predicting later language delay2,3. These factors have led to some arguing for a model of risk factors to be used when assessing late talkers4; but even in large population studies, these risk factors are only modestly successful at predicting which children will have long-term language impairments.

At Lancaster University, we have been studying a group of ~ 20 late talking children alongside 40 typically developing comparison children in-depth over the course of two years. We are looking at whether there are any clues in the way language is learned that might tell us why some late talkers catch up, and some do not. In particular, we have studied word learning and how children use language to support their understanding of the world. Despite our research being interrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic, we have discovered some interesting insights into these areas that we hope will help us understand more about late talking.

Firstly, despite the children in our study coming from broadly similar socioeconomic backgrounds and households, we still found a great deal of variation between children in their social skills, receptive vocabulary, and temperament (largely evident from testing sessions!), as well as issues such as parental concern and referral to specialist services.

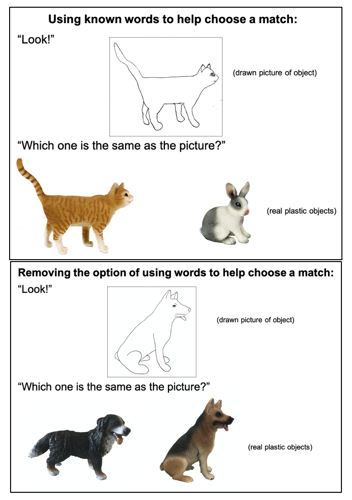

Secondly, despite there being a big difference in how many words our late talkers spoke compared to our typically developing group when we recruited them, any differences between the two groups proved much harder to pick out when we studied how they use their language skills to understand the world. We investigated how children use language to help them relate (2-dimensional) pictures to real (3-dimensional) objects (adapted from5). At age 2, the children were shown a simple picture of a familiar object such as a cat. They were then shown two model animals, such as a cat and a rabbit, and were then asked “which is the same as the picture?” (you can see an example of these trials in Figure 1).

If children recognise what the picture looks like, they can use the word ‘cat’ to help them correctly match the picture to the model cat rather than the bunny. Children with smaller vocabularies might find this task harder because they have fewer words to help them ‘sort’ what they see. We also examined children’s understanding of pictures when they are unable to use words to help match them to objects (e.g. selecting between two types of “dog”, such as a German Shepherd and a Burmese Mountain dog). We then repeated this task when the children were 3.5-years-old.

At 2-years-old, we found that our group of typically developing children were generally accurate at matching pictures to objects in this game, whereas the late talkers often appeared to be guessing at random. In particular, when they could use words to help them choose between objects, late talkers appeared to score lower than the typically developing children. When we played the game again when the children were 3.5-years-old, both groups were good at using words to help match pictures to the right objects. Curiously, we found that late talking at 2 years old did not predict how well children performed at 3.5-years-old, but the children’s spoken vocabulary 3.5-years-old did.

Overall, these results suggest that the differences between late talkers and non-late talkers, even at an early age, are subtle and varied (which is why we find it so hard to predict those who will catch up from those who will not). Although it seems as though the number of words a child says still has an effect on how children understand the world through our picture matching game, being a late talker at 2-years-old isn’t sufficient to tell us how that might affect children’s understanding later on. Similarly, studies that follow late talkers over a longer period of time find that they often reach the same range of vocabulary skills as typically developing children, but they tend to remain at the lower end of this range6. These studies suggest that early differences in children’s speech may continue to persist, but are hard to detect if we use a hard distinction between late talking and typically developing when studying how language helps children’s understanding of pictures and objects in the world.

Of course, further research is necessary with much larger samples to see whether our findings persist. Data collection is still in progress for our study and, although COVID-19 restrictions mean we cannot collect as much as we had hoped, when the study is complete we hope to shed some light on the individual differences between late talking children that make predicting their outcomes so difficult. These data include social ability, family structure, day-to-day living skills, birth history (e.g. prematurity, complications during pregnancy), how children link words to objects the first time they hear them and how well they remember them later (fast-mapping and retention), and how well children can repeat a word after hearing it for the first time (non-word repetition). So far, our research suggests that although most children who are late talkers at 2-years-old tend to catch up, talking still appears to affect how children process the world around them as they get older. However, much like DLD7,8, there is a great deal of variety in late talkers that supports a more nuanced approach when working with them clinically.

-

Rescorla, L. (2011). Late talkers: Do good predictors of outcome exist? Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 17, 141–150.

-

Henrichs, J., Rescorla, L., Schenk, J. J., Schmidt, H. G., Jaddoe, V. W. V., Hofman, A., Raat, H., Verhulst, F. C., & Tiemeier, H. (2011). Examining continuity of early expressive vocabulary development: The generation R study. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research: JSLHR, 54(3), 854–869.

-

Reilly, S., Wake, M., Ukoumunne, O. C., Bavin, E., Prior, M., Cini, E., Conway, L., Eadie, P., & Bretherton, L. (2010). Predicting Language Outcomes at 4 Years of Age: Findings From Early Language in Victoria Study. Pediatrics, peds.2010-0254.

-

Collisson, B. A., Graham, S. A., Preston, J. L., Rose, M. S., McDonald, S., & Tough, S. (2016). Risk and Protective Factors for Late Talking: An Epidemiologic Investigation. The Journal of Pediatrics, 172, 168-174.e1.

-

Callaghan, T. C. (2000). Factors affecting children’s graphic symbol use in the third year: Language, similarity, and iconicity. Cognitive Development, 15(2), 185–214.

-

Rescorla, L. (2009). Age 17 language and reading outcomes in late-talking toddlers: Support for a dimensional perspective on language delay. Journal Of Speech, Language, And Hearing Research: JSLHR, 52(1), 16–30.

-

McKean, C., Law, J., Morgan, A., & Reilly, S. (2018, August 23). Developmental Language Disorder. The Oxford Handbook of Psycholinguistics.

-

Leonard, L. (2018) Children with Specific Language Impairment, 2nd Edition. Cambridge, MA:The MIT Press.