Last month I submitted my PhD at the Lancaster University. As part of the LuCiD project, I investigated how infants use communicative signals, such as addressing a child by looking at them or speaking to them in so-called infant-directed speech changes. According to Natural Pedagogy, a widely discussed theory in developmental psychology, infants come to this world with a basic sensitivity towards signals that tell them that they are communicated with—and expect that adults engaging with them will show them something meaningful to learn and apply in other contexts. The first two studies that I did as part of my PhD looked at how addressing children before showing them an action increases children’s expectation that these actions are meaningful using EEG and eye tracking. For example, children expect an adult to put a spoon to the mouth, rather than the ear. But does looking and addressing children raise their expectation that the spoon should go to the mouth?

However, there is also another way that communicative signals can be useful in action learning. An important aspect of learning an action is understanding how to break it up into small chunks that can be made sense of. We already know that adults overemphasise action boundaries when demonstrating actions to their children, which might help them to break up actions. They are also more likely to look and speak to their children at the beginning and end of the units of longer action sequences. Therefore, communicative signals could provide another important source of information on actions, by providing information how an action is meant to be segmented. This also opens the fascinating possibility- could communicative signals bring meaning to actions by breaking them up into the right parts?

During the final year of my PhD I embarked on another study to answer this question at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in Leipzig. In September 2017, through a LuCiD travel award, I visited Professor Stefanie Hoehl’s Early Social Cognition research group. First I needed to find a suitable method. To understand how children segment actions, we needed an age-appropriate action consisting of multiple parts—which in turn could be interpreted differently depending on how they are segmented. I found a simple paradigm used in previous research by Carpenter et al1. They showed 12- and 18-month olds a mouse hopping or sliding into a house. When the children got to play with the mouse and the house, they only put the mouse into the house, but ignored the first part of the action, i.e. how the mouse moved, whether it was hopping or sliding. But when children of the same age were shown the hopping and the sliding action on its own, they were able to imitate it. Therefore, it’s not that they cannot do the action, they simply don’t seem to think it’s relevant when they see the mouse go into the house. So, what if we could use communicative signals to break up the manner of hopping and sliding from the outcome of putting the animal into the box? Could a simple look towards the child with an ambiguous word, such as `wow’ be sufficient in breaking up the manner and outcome, so that the manner can stand on its own and is imitated at the same rate by children?

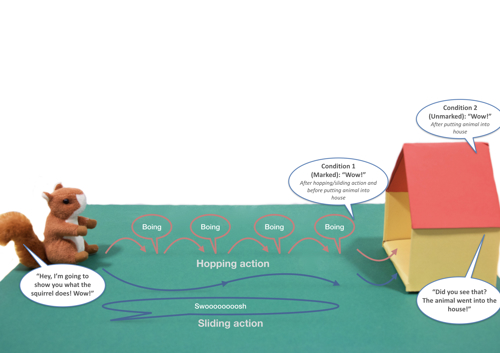

I recruited 40 children to take part in the study. For each test they were shown an animal (we used a fox, bunny, hedgehog and a squirrel to make it more fun for the kids) hopping or sliding into a toy house and were then asked to copy this. In half the tests I provided the communicative signal ‘wow’ after the hopping/sliding action (before the animal went into the house). In the other half of the tests, the ‘wow’ was uttered at the end of the sequence, after the animal went into the house. I predicted that the children would be unlikely to copy the manner of the action when they are addressed after the animal went into the house. However, when they are addressed after the hopping/sliding action, but before putting the animal into the house, they would be much more likely to imitate the manner.

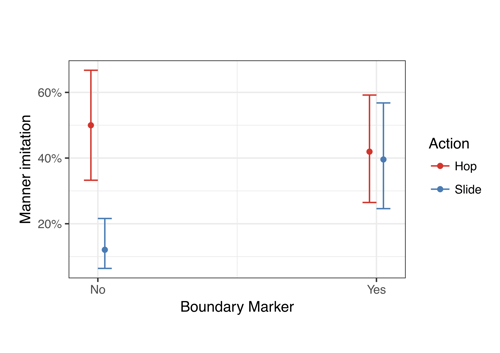

In fact I found that this only holds true for one of the actions. Children are actually not more likely to imitate the hopping action if I address them between the two action units, and both groups of children imitated the action 40-50% of the time. However, for the sliding action I did find a reliable difference depending on where within the action sequence I addressed them. If I addressed the children between the events, about 40% of the children imitated the sliding action. But if I addressed them after I put the animal into the house, only about 12% did.

This difference might not be that unexpected after all. The hopping action is a much more salient action on its own, and also highly repetitive. Because of this, children might have found it easy to see the action as meaningful in its own right. However, the sliding action is much less salient, and even though children tend to just pick up the animal and put it into the house, they might see sliding as merely instrumental in achieving the desired outcome of the animal in the house.

As always, the study raises some new questions, too. What is it about the hopping action that makes it stand out more? Is it its repetitiveness, or just because it’s fun to do? Are there more actions that can be categorised along these lines, and attributes of an action matter for determining whether or not children imitate these actions?

In the end, the three-month stay turned into more than a year, and I took up a job as a lab assistant at Professor Hoehl's lab. For this, I have collected EEG and behavioural data for about 90 infants and toddlers, and we are in the process of analysing this data set as well. I presented the study I described above at the LCICD Conference in Lancaster and the PINA conference in Potsdam and got lots of great feedback for future research. I also got to see the other exciting work Prof Hoehl’s group is doing, (you can read more about this in Han Ke's earlier blog). I’m very grateful for the opportunity that the travel exchange has offered me, and I’m excited to build upon the data that I collected during my stay in Leipzig.

References

1. Carpenter, M., Call, J., & Tomasello, M. (2005). Twelve and 18 month olds copy actions in terms of goals. Developmental Science, 8(1), F13-F20, DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2004.00385.x